Zofia Jaroszuk: When did you start thinking about Acid Rain?

Tomek Popakul: My main intention was to do something completely new. I felt that black‑and‑white, depressive films weren’t good for me anymore, so I wanted to do something I would be happy to work at, to choose a topic I like. I listen to electronic music and often go to parties with such music – they turned out to be the new subject of my film. The natural consequence of this choice was the inspiration connected mostly with the beginning of the rave scene in the world and its special Central‑European character. My goal was to show the atmosphere of those years – starting from fashion, through music up to the landscape, presenting the unique nature of this retro, post‑Communist style with its rawness and melancholy. I wanted to reconstruct the atmosphere of that time, which many people called the second summer of love, but this time in polyamide tracksuits, with stimulants, different colors and, above all, with louder and livelier music.

ZJ: Can you tell us more about the documentation work you did while working on the film?

TP: The research was both pleasant and rewarding. To me, the main reference was the notion of ‘duchologia’ (lit. spiritology) as popularized by Olga Drenda as the aesthetics of something of the past that was experienced as vague memories from childhood in which you actually never participated. Drenda connects this term with the years of transformation, where theremains of communist reality became mixed up with the blindly adopted capitalist system. The beginning of the rave scene and the start of electronic music in Poland coincided precisely with the beginning of freedom and with the moment when Polish people were excited about everything that was new. I personally remember this time dimly, but it became a strong point of reference for the film. While preparing myself for the film I conducted a series of interviews with my friends who remember the atmosphere of those years very well. However, the film is achronological and doesn’t take place in one specific moment – these are rather my ideas and visions of the nineties.

ZJ: Acid Rain is one of the first color films after black and white and monochromatic Ziegenort and Black. How did you worked on the color concept of the film and how did you achieve the retro effect in the picture?

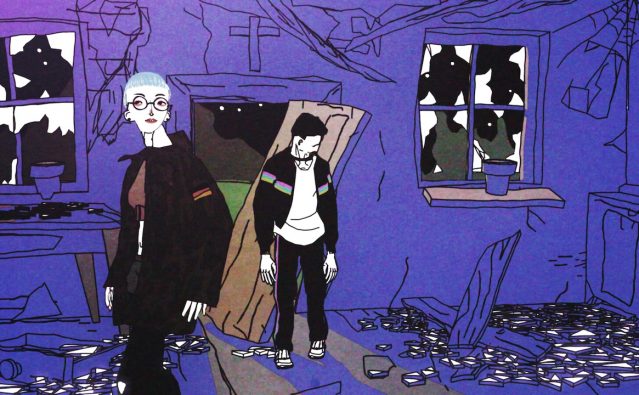

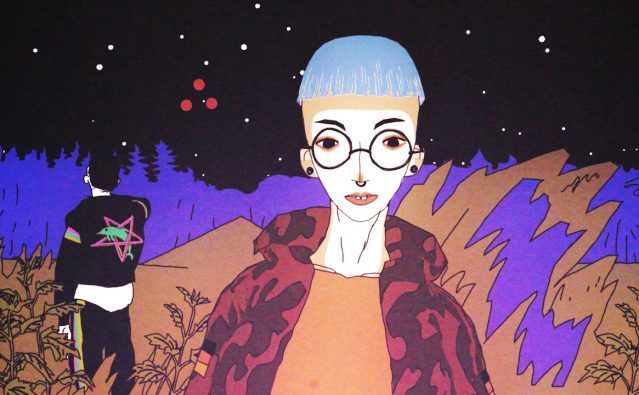

TP: Having control over colors was both a big problem and a challenge to me. Limiting the color range was a crucial issue. While working on this aspect, I watched old printing techniques, including Japanese art of woodcut, in which the technique imposes great restrictions on the artist, since every layer of the color is a separate copy. This restriction gives a very exceptional aesthetic effect that allows to avoid the color chaos. From the very beginning, I wanted Acid Rain to be strongly stylized. To achieve it, I used the colors of fluorescent paintings and gadgets characteristic for psytrance, combining them with shades of grey that reflect the shades of Eastern Europe with its messiness, rust and negligence. I connected those two palettes and this way I achieved the target colors of the film. Additionally, I cared about the effects of blurring and granularity while stylizing the picture. There is practically no blackness in the film because I consistently applied the effect of fading which can be compared to colors diluted with time.

ZJ: You make films, using a very original technique that connects the possibilities of 3D technology with 2D animation. It is a very time‑consuming technique. What does this tool give you in terms of art?

TP: In the technique I use, the possibility of working with a camera is important and this is exactly what 3D technology gives me. I talk with a camera a lot – I do matestershots and very film‑like shots, which are difficult to achieve in 2D animation due to the difficulty of some foreshortenings and captures that are terribly difficult to draw. The second and definitely more complicated stage of the work is to make a 3D material look similar to animation. Personally, I enjoy this stage the most. When it comes to visual arts, the most interesting reference for me is book illustration with flat colors, strong contours and the synthesis of shapes, so in my films I always try to achieve a similar effect.

ZJ: Let’s talk about the script for a while. The story you tell in Acid Rain is very plot‑oriented and one can clearly see the inspiration with such genres, as road movie or teenage movie.

TP: While thinking about the script I start with a strong image. In this case it was the scene, in which the protagonists swims in an overgrown pond, smokes a pipe and empties it out into a can. On one hand it is a very holiday image, and on the other hand it presents some element of degeneration, which, in my opinion, has determined the atmosphere of the film very well. I like genre cinema and I agree that Acid Rain is a road movie, and my aim was also to make it a teenage movie – one of my favorite genres of all. While starting with a certain genre, I like to mess with it in order to break the convention. I like simple constructions and strong relationships. I usually play my stories between two protagonists: a boy and a girl whose relationship is undefined. There is always a third figure who spoils this relationship. While working on the script, I always try to write a couple of strong scenes which the viewer will remember after leaving the cinema. The next stage is to weave those scenes and elements into the thread of a consistent plot.

ZJ: The film is also recognizable due to a fantastic soundtrack. You also make music, beside making animation. Why you didn’t make the music to this film yourself?

TP: I didn’t make the music to this film, since I wanted to use the work on the film as an opportunity to get in touch with people who I admire and have been listening to for ages. Amongst the artists you can here in the film, there is Jerome Hill – a veteran of this genre, Andy Jenkinson – a cult author of acid pieces working under the pseudonym Ceephax Acid Crew or Lou Karsh from Australia who proves that nostalgia for the 1990s is still alive and well. Despite his young age, Lou creates pieces which are taken straight from that time. While choosing the music of Polish authors, I reached for the pieces of a friend of mine – Artur Oleś – Chino and Karol Su/Ki, whose pieces are deeply rooted in that time, place and state of mind. I’m really happy that he agreed for his music to be used in the film.

ZJ: Since January, the film has been presented at festivals, receiving awards and the recognition of both critics and audience alike. What emotions did you feel before the first screenings?

TP: During every screening, I feel a bit nervous, since there are some controversial scenes in the film. I really calmed down when some girls came to me after the screening and said they had understood the motivation of the main character or that they were in a similar relationship. I was anxious about whether I would be able to show the female character in the film fairly, and this is why I was glad to hear those first reactions. I wanted the film to be fast, colorful, loud and full of pop culture and I have the impression that I succeeded, evidence being the two audience awards the film received. To me, this is the only true, unquestionable award. Here, the situation is simple and you can compare it to dance parties – people either like whatyou do and dance or they go outside to smoke a cigarette.

“Focus on Poland” Magazine 9 (1/2019)